Federal and State Push for Universal Preschool Is Welcome News for K-12

As the federal government and states begin the process of setting next year’s budget, many are focusing on early childhood. Earlier this year, President Joseph Biden advocated for universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds in the State of the Union address, before including free universal pre-K for all 4-year-olds and grants to expand preschool for 3-year-olds in his budget proposal. In Massachusetts, Gov. Maura Healey announced “Gateway to Pre-K,” a plan to give universal pre-K access to 4-year-olds in 26 cities, while Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer proposed making preschool free for all young children in the state. Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear’s latest budget proposal includes funding to stabilize the child-care system and start a new universal pre-K program for 4-year-olds.

This is all welcome news, not only for parents and advocates of early childhood education, but for those who work in K-12 education. I taught middle and high school, so people are often surprised that the education policy I champion the most is not about teenagers — it’s universal early childhood education. I often wished that my students could have been given a stronger and more equitable start early on, rather than needing interventions in later grades to address issues associated with childhood trauma from poverty and racism. Research shows that most brain development occurs in the first five years of a child’s life, and there is overwhelming evidence that high-quality early childhood education leads to long-term positive academic, economic, and health outcomes.

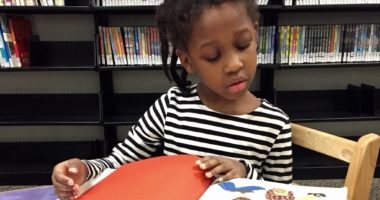

Yet children from low-income backgrounds and children of color — who are disproportionately likely to live in low-income households — are significantly less likely to attend preschool than their peers, due to high costs, the short supply of available spots, and barriers to applying for and receiving child-care subsidies. Despite existing federal aid programs, the Department of Health and Human Services estimates that 77% of children who are eligible for child care and early education program subsidies do not actually receive them. Additionally, census data shows that preschool enrollment declined significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many child-care centers closed and costs rose. Young children from low-income families and young children of color were particularly hard hit, with rates for Black, Latino, and Asian children declining more than the rate for white children.

Many of these young children are experiencing adversity because of poverty and systemic racism and would benefit most from attending a high-quality preschool. Gaps between children living in poverty and more affluent children can be observed as early as age 4, and the inequities we see in K-12 education take root long before children enter kindergarten.

High-quality early childhood education has been shown to promote positive brain development and mitigate the effects of adverse experiences in young children. Investing in children earlier can reduce opportunity gaps and educational inequities and help students develop the social, emotional, and learning skills that they’ll need later. Having a strong foundation in language development sets the stage for children to become proficient readers in later grades, and having stable learning environments and relationships in early childhood helps them build resilience in the face of adversity and cope with trauma, so they can learn without disruption. Investing in early education also helps ensure that students don’t enter kindergarten behind their peers academically, averts the need for intervention later on to correct the effects of an education system that’s failing low-income students and students of color, and sets these students up to stay on grade level throughout their K-12 education, graduate high school, and go on to pursue a postsecondary education.

Politicians and members of the media rightfully note that quality preschool programs benefit parents and caregivers, too. Having access to high-quality preschool and stable child care lets working parents, especially working mothers, stay in the workforce, instead of having to choose between child care and a career. Research shows that mothers of children enrolled in early childhood education typically have higher incomes and better long-term economic stability. It also benefits student parents and sibling caregivers whose education might otherwise be disrupted due to a lack of child care. This two-generation impact is certainly a benefit, but the long-term positive effects for children speak for themselves.

Of course, making universal high-quality early childhood education a reality will necessitate addressing challenges like widespread staff shortages, low wages for educators, and the risk of additional child-care disruptions and shortages as the end of COVID-19 federal relief funding forces more providers to close. It will also require strategic workforce planning, in addition to a long-term financial commitment, but the positive effects that persist through K-12, higher education, and into adulthood have been shown to have a high impact and a huge return on investment. Failing to invest in these crucial early childhood years, when a huge amount of brain and language development occurs, would be shortsighted, since preschool programs can offset the negative effects of inequities early on and yield big long-term benefits.

Haley Steed is a LEE Public Policy Fellow at EdTrust